В началото на 2016 Англия за пореден път беше ударена от сериозни наводнения. Те са не само следствие от глобалните климатични измамения, но и от нарастващата урбанизация на заливните тераси на реките. Един град обаче прави изключение. Въпреки че е разположен на изключително уязвимо от гледна точка на водите място, тази година той беше спасен. Според статия на Индипендът това се дължи на интелигентната защита, изразяваща се в защитни системи, използващи принципите на природата. Според статия Гардиан, обяснението е, че просто тази година не е валяло толкова много. След съпоставяне и на двата текста обаче се вижда, че изведените заглавия търсят сензацията, а истината е еднозначна – трябва да търсим природосъобразните решения, за да намалим риска от наводнения. Това е единственият път. За съжаление обаче дори тези решения няма да са достатъчни при все повече увеличаващият се риск, предизвикан от глобалните климатични процеси. Нашият нестихващ интерес да се заселваме все по-близо до реките ще продължи да изисква серия от инженерни решения, за да можем да управляваме риска. Но цената вече става прекомерна.

Ето и конкретните текстове

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/uk-flooding-how-a-yorkshire-flood-blackspot-worked-with-nature-to-stay-dry-a6794286.html

Ето и конкретните текстове

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/uk-flooding-how-a-yorkshire-flood-blackspot-worked-with-nature-to-stay-dry-a6794286.html

Pickering pulled off protection by embracing the very opposite of what passes for conventional wisdom

While the sodden, submerged North of Britain was, literally, wringing out the old year last week, one notorious Yorkshire flood blackspot was celebrating staying dry – despite having been refused a multimillion pound defence scheme.

Pickering, North Yorkshire, pulled off protection by embracing the very opposite of what passes for conventional wisdom. On its citizens’ own initiative, it ended repeated inundation by working with nature, not against it.

Its success, and that of similar schemes across the country, should be at the heart of the “complete rethink” of policy being officially promised in the aftermath of last month’s floods – which cost the country at least £5 billion – as climate change threatens to make them increasingly commonplace.

And it ridicules an increasingly-voiced contention that these were largely caused by what one columnist called “militant environmentalism” enforced by “green zealots who put protected species above people”. By this argument, much advanced by climate change sceptics, the unprecedented north English and Scottish inundations – like those on the Somerset Levels and the Thames Valley two years ago – are down to successive Governments and officials neglecting to take precautionary measures, like dredging rivers, in order to protect wildlife.

If this were true, few places would have better reason than Pickering to want to keep nature at bay. Stuck at the bottom of a steep gorge draining much of the North Yorks Moors, it was flooded four times between 1999 and 2007, with the last disaster doing £7 million of damage.

The solution, its people were officially told, would to be build a £20 million concrete wall through the centre of town to keep the water in the river. No-one thought it was ideal: it would have impaired Pickering’s attraction for tourism. But then they were told that they could not have it anyway since too few people would be protected to satisfy the cost-benefit analysis for such schemes enforced on the Environment Agency by the Treasury.

At that point – as Mike Potter, chairman of the Pickering and District Civic Society puts it – the townspeople were “spitting feathers” and decided to take matters into their own hands. Hearing from a local environmentalist how the moors had traditionally released rainwater much more slowly – and of how, centuries ago, monks at nearby Byland Abbey had built a bund to hold it back – they decided to try to go back to the future.

They got together with top academics from Oxford, Newcastle and Durham Universities to examine all options. Much the best plan turned out indeed to be to try to recreate past conditions by slowing the flow of water from the hills. Impressed by the intellectual endorsement, official bodies like the local councils, the Environment Agency, the Forestry Commission and even the Department of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, joined in.

They built 167 leaky dams of logs and branches – which let normal flows through but restrict and slow down high ones – in the becks above the town; added 187 lesser obstructions, made of bales of heather and fulfilling the same purpose, in smaller drains and gullies; and planted 29 hectares of woodland. And, after much bureaucratic tangling, they built a bund, to store up to 120,000 cubic metres of floodwater, releasing it slowly through a culvert.

After 24 hours of rain, just three months after it was inaugurated, Mr Potter climbed up to the scheme and found it working well. Then he went home, “switched on the TV, and saw the all the floodwaters elsewhere”. He adds: “While there was devastation all over northern England, our newly completed defences worked a treat and our community got on with life as normal.” The total cost, he says, was around £2m, a 10th that of the original wall which, he believes, would not have coped with the Boxing Day conditions anyway.

Nor is Pickering alone. A more high-tech scheme, but operating on the same principle, has successfully slowed floodwaters near Glasgow. Building porous wooden dams, and blocking ditches, saved the floodprone Somerset villages of Bossington and Allerford while the Levels flooded two years ago. And the Potteric Carr nature reserve, designed to store floodwater, kept the south of Doncaster dry, even as the north of the city went underwater, in the great floods of 2007.

Such schemes are not the whole solution. Sarah Whatmore, Professor of Environment and Public Policy at Oxford University – who led the academic work in Pickering – says they will often be of most benefit to small communities who do not qualify for more expensive interventions.

And certainly the government should do more to build conventional defences. It is a scandal that both it, and the conservative-led coalition, should have cut spending on them – despite promises – including postponing schemes, as in Kendal and Leeds, that could have cut December’s devastation. After all, flood defences return £8 for each £1 invested – a ratio that, say, High Speed 2 would die for – and even the Treasury admits that building them “helps drive growth”.

And much more is going to be needed as climate change takes hold. A study, published last week by Oxford University and the Royal Netherlands Metereological Institute, found that global warming made the floods caused by Storm Desmond last month some 40 per cent more likely. Scientists agree they will increase as the world heats up.

We should also stop making ourselves more vulnerable. Half the houses built in Britain in the last 60 years have been plonked onto floodplains, and twice as many are still being built on them as elsewhere.

Even more important, though less publicised, is the need to stop denuding the countryside. Traditionally it – and especially uplands – have acted as a giant sponge, soaking up rainwater and releasing it gently, preventing floods and easing droughts. But even as our officials have tramped round developing countries, urging the importance of maintaining forests and wetlands for this purpose, other branches of government have promoted their destruction at home. The peaty soil of bogs, for example, can be nine-10ths water, but they have been drained and taken to mulch millions of gardens. Trees enable rainwater to penetrate the ground 60 times faster than grassland, but Britain has become one of the least wooded countries in Europe. Too many sheep graze hillsides bare and compact their soil with their hooves, causing rain to sheet off them, yet farmers have been encouraged to overstock.

Heather is burned, with government grants, to ‘improve” grouse moors, reducing their ability to retain water. Land left bare between crops also causes rain to run off, eroding the soil; hence the chocolate colour of a flooding river. Maize is probably the most destructive of all – a study of over 3000 sites growing it showed three quarters to be seriously degraded and shedding water – yet it is officially exempted from soil conservation rules governing other crops.

It is the same story in town. As gardens disappear under impervious concrete and decking, stormwater runs off into sewers that can’t accommodate it: in London alone, the Wildlife Trusts found land equivalent to two-and-a-half Hyde Parks is lost this way each year. Back in 2010 the Measures to ensure that new developments minimised run-off with “sustainable drainage systems” were enacted in 2010. But the Coalition repeatedly delayed implementing them, then scrapped them.

So, despite the mythology, it is destroying nature that causes floods, while protecting it prevents them. The much-touted dredging can be useful in some places, but generally makes things worse by speeding up river flow and causing more trouble downstream. And it is only removing silt produced upstream from soil erosion that should be prevented in the first place.

Many small scale-efforts are being made, as at Pickering. Blocking ditches in Montgomeryshire has increased the water holding capacity of a 1,100 hectare catchment area by 155 million litres. Restoring Devon’s Culm grasslands, by the local Wildlife Trust, quintupled the land’s water retention. But natural flood protection needs to happen on a national scale – as it has in the Netherlands the very home of the dyke, for two decades.

Some environmentalists want to slash support for farmers. It would be far better to direct it to reducing flooding by, for example, supporting tree planting and retaining wetlands, and paying landowners to set aside relatively unproductive land to take excess water so as to avoid inundation downstream.

But David Cameron last year allowed EU grants going to such environmentally-friendly purposes to be cut – despite pleas even from his distinctly ungreen environment secretary, Owen Paterson. “Why” he said, spectacularly missing the point “should we be the only saint in the brothel?”

Perhaps, just perhaps, the recent floods will shift such – shall we say – antediluvian attitudes. Opening the Pickering scheme in September, Environment Secretary Liz Truss said “we can use the results we get here much more widely”. Let’s hope (against hope) that she meant it.

So-called natural flood defence schemes are an attractive idea, but they would be powerless in the face of extreme weather

The town of Pickering is a notorious flood spot in the north-east of England, on the edge of the North York moors. So when the town escaped flooding this Christmas while York – just 40 miles away – was underwater, it seemed an open and shut case. Surely, it was the recently opened “working with nature” flood defence scheme above Pickering that saved the town? For the many advocates of the benefits of working with nature it seemed a great vindication.

The town of Pickering is a notorious flood spot in the north-east of England, on the edge of the North York moors. So when the town escaped flooding this Christmas while York – just 40 miles away – was underwater, it seemed an open and shut case. Surely, it was the recently opened “working with nature” flood defence scheme above Pickering that saved the town? For the many advocates of the benefits of working with nature it seemed a great vindication.

And when the Independent published Geoffrey Lean’s convincing article on the “town that escaped the flood”, it became an environmental sensation, with everyone from Chris Packham to former Tory environment minister Richard Benyon tweeting the story.

The only problem with this was that the town didn’t flood because of the flood scheme - but because it didn’t rain much at Christmas in Pickering.

In fact, the North York moors – where the water that floods Pickering comes from - were an anomalously dry spot in the whole of the north of England. It’s possible to see this even in the Met Office’s provisional December 2015 rainfall summary, and clearer still in the data from the weather station at Westerdale. All tell the same story – it did rain, but only a modest amount above the average.

Working with nature to hold back floodwater - by measures like planting trees or renaturalising landscapes to store or absorb more water - is an attractive idea we all hope may be part of a future solution. But with something as important as flooding - where people’s lives and livelihoods are at stake - it’s vital not to jump to conclusions too quickly.

In practice, compared to conventional methods (for example, using walls on the floodplain to constrain floods, or dredging channels to speed the water through), the UK doesn’t really have much experience of using more natural landscape absorption methods yet.

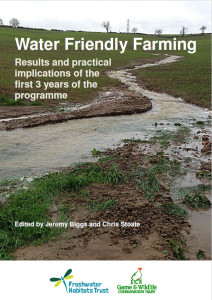

Our own Water Friendly Farmingproject, with partners University of York and Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust, funded by the Environment Agency, is investigating this same problem. Our field studies and modelling help provide a reality check.

Working in typical lowland English countryside, in catchments each covering about 10 square kilometres, we find that even if we completely covered the catchments with trees, it would at best reduce the one-in-100 year flood peak by about 15-20% . This is similar to the levels expected in Pickering’s Slowing the Flow programme. In both cases, the flood protection effect would be useful - but if it really pours, the landscapes would be overwhelmed.

So are there other answers? In places where large floodplains can be adapted to temporarily store billions of litres of water the effect could be much bigger. We see the potential for this in models created for our Water Friendly Farming test areas in Leicestershire. We are also seeing some of the first benefits for combining flood protection and wildlife benefits in the landscape: when we add new clean-water ponds to the landscape, it reversed the loss of freshwater plants in the countryside, one of the first demonstrations that this is possible.

The real story here is that working with nature has the potential to be a valuable new approach which, if methods are used extensively and in combination, could help reduce the impacts of large floods events.

But we need to admit that extreme events may always be beyond the control of any measures in the flood control armoury. If designed carefully natural flood control methods may also bring other benefits for wildlife and things like countryside access. But we are a long way from that yet.

In the meantime, the natural flood control approach urgently needs better modelling tools that link land use models to flood models – a thing that is only just beginning in the UK. We need to combine this with more largescale landscape trials and more rigorous and honest assessment of their value, so we don’t rush blindly into creating follies in the countryside before we have a clearer and more integrated understanding of how well they will work.

• This article was amended on 19 January 2016 to remove a suggestion that Geoffrey Lean did not check his facts. He did so and he sets out his argument that Pickering did get significant rainfall over Christmas in a blog here.

Няма коментари:

Публикуване на коментар